Perspectives on Abnormal Behavior

2.2 Therapeutic Orientations

Hannah Boettcher; Stefan G. Hofmann; Q. Jade Wu; Alexis Bridley & Lee W. Daffin Jr.; Carrie Cuttler; and Jorden A. Cummings

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the similarities and differences between theoretical orientations and therapeutic orientations

- Explain how the following orientations view abnormality and suggest we treat it: Psychodynamic/psychoanalytic, person-centered, behavioural, cognitive, cognitive behavioural, acceptance-based, and mindfulness-based

- Discuss emerging treatment strategies

What are Theoretical Orientations?

Although all psychologists share a common goal of seeking to understand human behaviour, psychology is a diverse discipline, in which many different ways of viewing human behaviour have developed. Those views are impacted by the cultural and historical context they exist within, as we have previously discussed in earlier sections of this book.

The purpose of a theoretical orientation is to present a framework through which to understand, organize, and predict human behaviour. Theoretical orientations explain, from that orientation’s perspective, why humans act the way they do. Applied to mental health, they are often referred to as therapeutic orientations and serve to also provide a framework for how to treat psychopathology. You can think of each orientation as a different pair of coloured glasses through which we view human behaviour. Each orientation will see human behaviour slightly differently, and thus have a different explanation for why people act the way they do. When applied to treatment, this means that each orientation might recommend different types of interventions for the same disorder.

Practicing mental health workers, like clinical psychologists, generally adopt a theoretical orientation that they feel best explains human behaviour and thus helps them treat their clients and patients. For example, as you will see below, a psychodynamic therapist will have a very different explanation for a client’s presenting problem than a behaviour therapist would, and as such each would choose different techniques to treat that presenting problem. In this section we’ll discuss some of the major theoretical/therapeutic orientations, how they view human behaviour and treatment, and what techniques they might use.

Psychoanalysis and Psychodynamic Therapy

The earliest organized therapy for mental disorders was psychoanalysis. Made famous in the early 20th century by one of the best-known clinicians of all time, Sigmund Freud, this approach sees mental health problems as rooted in unconscious conflicts and desires. In order to resolve the mental illness, then, these unconscious struggles must be identified and addressed. Psychoanalysis often does this through exploring one’s early childhood experiences that may have continuing repercussions on one’s mental health in the present and later in life. Psychoanalysis is an intensive, long-term approach in which patients and therapists may meet multiple times per week, often for many years.

Freud suggested more generally that psychiatric problems are the result of tension between different parts of the mind: the id, the superego, and the ego. In Freud’s structural model, the id represents pleasure-driven unconscious urges (e.g., our animalistic desires for sex and aggression), while the superego is the semi-conscious part of the mind where morals and societal judgment are internalized (e.g., the part of you that automatically knows how society expects you to behave). The ego—also partly conscious—mediates between the id and superego. Freud believed that bringing unconscious struggles like these (where the id demands one thing and the superego another) into conscious awareness would relieve the stress of the conflict (Freud, 1920/1955)—which became the goal of psychoanalytic therapy.

Although psychoanalysis is still practiced today, it has largely been replaced by the more broadly defined psychodynamic therapy. This latter approach has the same basic tenets as psychoanalysis, but is briefer, makes more of an effort to put clients in their social and interpersonal context, and focuses more on relieving psychological distress than on changing the person.

Techniques in Psychoanalysis

Psychoanalysts and psychodynamic therapists employ several techniques to explore patients’ unconscious mind. One common technique is called free association. Here, the patient shares any and all thoughts that come to mind, without attempting to organize or censor them in any way. For example, if you took a pen and paper and just wrote down whatever came into your head, letting one thought lead to the next without allowing conscious criticism to shape what you were writing, you would be doing free association. The analyst then uses his or her expertise to discern patterns or underlying meaning in the patient’s thoughts.

Sometimes, free association exercises are applied specifically to childhood recollections. That is, psychoanalysts believe a person’s childhood relationships with caregivers often determine the way that person relates to others, and predicts later psychiatric difficulties. Thus, exploring these childhood memories, through free association or otherwise, can provide therapists with insights into a patient’s psychological makeup.

Because we don’t always have the ability to consciously recall these deep memories, psychoanalysts also discuss their patients’ dreams. In Freudian theory, dreams contain not only manifest (or literal) content, but also latent (or symbolic) content (Freud, 1900; 1955). For example, someone may have a dream that his/her teeth are falling out—the manifest or actual content of the dream. However, dreaming that one’s teeth are falling out could be a reflection of the person’s unconscious concern about losing his or her physical attractiveness—the latent or metaphorical content of the dream. It is the therapist’s job to help discover the latent content underlying one’s manifest content through dream analysis.

In psychoanalytic and psychodynamic therapy, the therapist plays a receptive role—interpreting the patient’s thoughts and behavior based on clinical experience and psychoanalytic theory. For example, if during therapy a patient begins to express unjustified anger toward the therapist, the therapist may recognize this as an act of transference. That is, the patient may be displacing feelings for people in his or her life (e.g., anger toward a parent) onto the therapist. At the same time, though, the therapist has to be aware of his or her own thoughts and emotions, for, in a related process, called countertransference, the therapist may displace his/her own emotions onto the patient.

The key to psychoanalytic theory is to have patients uncover the buried, conflicting content of their mind, and therapists use various tactics—such as seating patients to face away from them—to promote a freer self-disclosure. And, as a therapist spends more time with a patient, the therapist can come to view his or her relationship with the patient as another reflection of the patient’s mind.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Psychoanalytic Therapy

Psychoanalysis was once the only type of psychotherapy available, but presently the number of therapists practicing this approach is decreasing around the world. Psychoanalysis is not appropriate for some types of patients, including those with severe psychopathology or intellectual disability. Further, psychoanalysis is often expensive because treatment usually lasts many years. Still, some patients and therapists find the prolonged and detailed analysis very rewarding.

Perhaps the greatest disadvantage of psychoanalysis and related approaches is the lack of empirical support for their effectiveness. The limited research that has been conducted on these treatments suggests that they do not reliably lead to better mental health outcomes (e.g., Driessen et al., 2010). And, although there are some reviews that seem to indicate that long-term psychodynamic therapies might be beneficial (e.g., Leichsenring & Rabung, 2008), other researchers have questioned the validity of these reviews. Nevertheless, psychoanalytic theory was history’s first attempt at formal treatment of mental illness, setting the stage for the more modern approaches used today.

Humanistic and Person-Centered Therapy

One of the next developments in therapy for mental illness, which arrived in the mid-20th century, is called humanistic or person-centered therapy (PCT). Here, the belief is that mental health problems result from an inconsistency between patients’ behavior and their true personal identity. Thus, the goal of PCT is to create conditions under which patients can discover their self-worth, feel comfortable exploring their own identity, and alter their behavior to better reflect this identity.

PCT was developed by a psychologist named Carl Rogers, during a time of significant growth in the movements of humanistic theory and human potential. These perspectives were based on the idea that humans have an inherent drive to realize and express their own capabilities and creativity. Rogers, in particular, believed that all people have the potential to change and improve, and that the role of therapists is to foster self-understanding in an environment where adaptive change is most likely to occur (Rogers, 1951). Rogers suggested that the therapist and patient must engage in a genuine, egalitarian relationship in which the therapist is nonjudgmental and empathetic. In PCT, the patient should experience both a vulnerability to anxiety, which motivates the desire to change, and an appreciation for the therapist’s support.

Techniques in Person-Centered Therapy

Humanistic and person-centered therapy, like psychoanalysis, involves a largely unstructured conversation between the therapist and the patient. Unlike psychoanalysis, though, a therapist using PCT takes a passive role, guiding the patient toward his or her own self-discovery. Rogers’s original name for PCT was non-directive therapy, and this notion is reflected in the flexibility found in PCT. Therapists do not try to change patients’ thoughts or behaviors directly. Rather, their role is to provide the therapeutic relationship as a platform for personal growth. In these kinds of sessions, the therapist tends only to ask questions and doesn’t provide any judgment or interpretation of what the patient says. Instead, the therapist is present to provide a safe and encouraging environment for the person to explore these issues for him- or herself.

An important aspect of the PCT relationship is the therapist’s unconditional positive regard for the patient’s feelings and behaviors. That is, the therapist is never to condemn or criticize the patient for what s/he has done or thought; the therapist is only to express warmth and empathy. This creates an environment free of approval or disapproval, where patients come to appreciate their value and to behave in ways that are congruent with their own identity.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Person-Centered Therapy

One key advantage of person-centered therapy is that it is highly acceptable to patients. In other words, people tend to find the supportive, flexible environment of this approach very rewarding. Furthermore, some of the themes of PCT translate well to other therapeutic approaches. For example, most therapists of any orientation find that clients respond well to being treated with nonjudgmental empathy. The main disadvantage to PCT, however, is that findings about its effectiveness are mixed. One possibility for this could be that the treatment is primarily based on unspecific treatment factors. That is, rather than using therapeutic techniques that are specific to the patient and the mental problem (i.e., specific treatment factors), the therapy focuses on techniques that can be applied to anyone (e.g., establishing a good relationship with the patient) (Cuijpers et al., 2012; Friedli, King, Lloyd, & Horder, 1997). Similar to how “one-size-fits-all” doesn’t really fit every person, PCT uses the same practices for everyone, which may work for some people but not others. Further research is necessary to evaluate its utility as a therapeutic approach. It is important to note, however, that many practitioners incorporate Rogerian concepts, like unconditional positive regard, into their work even if they primarily practice from a different theoretical orientation.

The Behavioural Model

The Behaviourists believed that how we act is learned – we continue to act in the ways that we are reinforced and we avoid acting in ways that result in us being punished. Likewise, they believed that abnormal behaviour resulted from learning and could be treated by learning via new reinforcements and punishments. Early behaviourists identified a number of ways of learning: First, conditioning, a type of associative learning, occurs which two events are linked and has two forms – classical conditioning, or linking together two types of stimuli, and operant conditioning, or linking together a response with its consequence. Second, observational learning occurs when we learn by observing the world around us.

We should also note the existence of non-associative learning or when there is no linking of information or observing the actions of others around you. Types include habituation, or when we simply stop responding to repetitive and harmless stimuli in our environment such as a fan running in your laptop as you work on a paper, and sensitization, or when our reactions are increased due to a strong stimulus, such as an individual who experienced a mugging and now experiences panic when someone walks up behind him/her on the street.

One of the most famous studies in psychology was conducted by Watson and Rayner (1920). Essentially, they wanted to explore the possibility of conditioning emotional responses. The researchers ran a 9-month-old child, known as Little Albert, through a series of trials in which he was exposed to a white rat. At first, he showed no response except curiosity. Then the researchers began to make a loud sound (UCS) whenever the rat was presented. Little Albert exhibited the normal fear response to this sound. After several conditioning trials like these, Albert responded with fear to the mere presence of the white rat.

As fears can be learned, so too they can be unlearned. Considered the follow-up to Watson and Rayner (1920), Jones (1924) wanted to see if a child (named Peter) who learned to be afraid of white rabbits could be conditioned to become unafraid of them. Simply, she placed Peter in one end of a room and then brought in the rabbit. The rabbit was far enough away so as to not cause distress. Then, Jones gave Peter some pleasant food (i.e., something sweet such as cookies; remember the response to the food is unlearned). She continued this procedure with the rabbit being brought in a bit closer each time until eventually, Peter did not respond with distress to the rabbit. This process is called counterconditioning or extinction, or the reversal of previous learning.

Operant conditioning, is more directly relevant to therapeutic work. Operant conditioning is a type of associate learning which focuses on consequences that follow a response or behavior that we make (anything we do, say, or think/feel) and whether it makes a behavior more or less likely to occur. Skinner talked about contingencies or when one thing occurs due to another. Think of it as an If-Then statement. If I do X then Y will happen. For operant conditioning, this means that if I make a behavior, then a specific consequence will follow. The events (response and consequence) are linked in time.

What form do these consequences take? There are two main ways they can present themselves.

-

- Reinforcement – Due to the consequence, a behavior/response is more likely to occur in the future. It is strengthened.

- Punishment – Due to the consequence, a behavior/response is less likely to occur in the future. It is weakened.

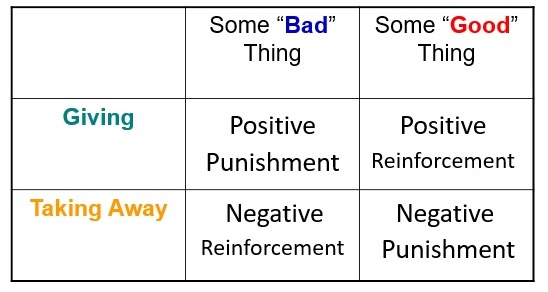

Reinforcement and punishment can occur as two types – positive and negative. These words have no affective connotation to them meaning they do not imply good or bad. Positive means that you are giving something – good or bad. Negative means that something is being taken away – good or bad. Check out the figure below for how these contingencies are arranged.

Figure 2.1. Contingencies in Operant Conditioning

Let’s go through each:

- Positive Punishment (PP) – If something bad or aversive is given or added, then the behavior is less likely to occur in the future. If you talk back to your mother and she slaps your mouth, this is a PP. Your response of talking back led to the consequence of the aversive slap being delivered or given to your face. Ouch!!!

- Positive Reinforcement (PR) – If something good is given or added, then the behavior is more likely to occur in the future. If you study hard and earn an A on your exam, you will be more likely to study hard in the future. Similarly, your parents may give you money for your stellar performance. Cha Ching!!!

- Negative Reinforcement (NR) – This is a tough one for students to comprehend because the terms don’t seem to go together and are counterintuitive. But it is really simple and you experience NR all the time. This is when you are more likely to engage in a behavior that has resulted in the removal of something aversive in the past. For instance, what do you do if you have a headache? You likely answered take Tylenol. If you do this and the headache goes away, you will take Tylenol in the future when you have a headache. Another example is continually smoking marijuana because it temporarily decreases feelings of anxiety. The behavior of smoking marijuana is being reinforced because it reduces a negative state.

- Negative Punishment (NP) – This is when something good is taken away or subtracted making a behavior less likely in the future. If you are late to class and your professor deducts 5 points from your final grade (the points are something good and the loss is negative), you will hopefully be on time in all subsequent classes. Another example is taking away a child’s allowance when he misbehaves.

Techniques in Behaviour Therapy

Within the context of abnormal behavior or psychopathology, the behavioral perspective is useful because it suggests that maladaptive behavior occurs when learning goes awry. As you will see throughout this book, a large number of treatment techniques have been developed from the behavioural model and proven to be effective over the years. For example, desensitization (Wolpe, 1997) teaches clients to respond calmly to fear-producing stimuli. It begins with the individual learning a relaxation technique such as diaphragmatic breathing. Next, a fear hierarchy, or list of feared objects and situations, is constructed in which the individual moves from least to most feared. Finally, the individual either imagines (systematic) or experiences in real life (in-vivo) each object or scenario from the hierarchy and uses the relaxation technique while doing so. This represents individual pairings of feared object or situation and relaxation and so if there are 10 objects/situations in the list, the client will experience ten such pairings and eventually be able to face each without fear. Outside of phobias, desensitization has been shown to be effective in the treatment of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder symptoms (Hakimian and D’Souza, 2016) and limitedly with the treatment of depression that is co-morbid with OCD (Masoumeh and Lancy, 2016).

Critics of the behavioral perspective point out that it oversimplifies behavior and often ignores inner determinants of behavior. Behaviorism has also been accused of being mechanistic and seeing people as machines. Watson and Skinner defined behavior as what we do or say, but later, behaviorists added what we think or feel. In terms of the latter, cognitive behavior modification procedures arose after the 1960s along with the rise of cognitive psychology. This led to a cognitive-behavioral perspective which combines concepts from the behavioral and cognitive models. After reviewing the basics of the cognitive model, we’ll discuss the cognitive-behavioural model in more detail.

The Cognitive Model

Behaviorism said psychology was to be the study of observable behavior, and any reference to cognitive processes was dismissed as this was not overt, but covert according to Watson and later Skinner. Of course, removing cognition from the study of psychology ignored an important part of what makes us human and separates us from the rest of the animal kingdom. Fortunately, the work of George Miller, Albert Ellis, Aaron Beck, and Ulrich Neisser demonstrated the importance of cognitive abilities in understanding thoughts, behaviors, and emotions, and in the case of psychopathology, they helped to show that people can create their own problems by how they come to interpret events experienced in the world around them. How so? According to the cognitive model, irrational or dysfunctional thought patterns can be the basis of psychopathology. Throughout this book, we will discuss several treatment strategies that are used to change unwanted, maladaptive cognitions, whether they are present as an excess such as with paranoia, suicidal ideation, or feelings of worthlessness; or as a deficit such as with self-confidence and self-efficacy. More specifically, cognitive distortions/maladaptive cognitions can take the following forms:

- Overgeneralizing – You see a larger pattern of negatives based on one event.

- What if? – Asking yourself what if something happens without being satisfied by any of the answers.

- Blaming – Focusing on someone else as the source of your negative feelings and not taking any responsibility for changing yourself.

- Personalizing – Blaming yourself for negative events rather than seeing the role that others play.

- Inability to disconfirm – Ignoring any evidence that may contradict your maladaptive cognition.

- Regret orientation – Focusing on what you could have done better in the past rather than on making an improvement now.

- Dichotomous thinking – Viewing people or events in all-or-nothing terms.

For more on cognitive distortions, check out this website: http://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/20-cognitive-distortions-and-how-they-affect-your-life-0407154

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

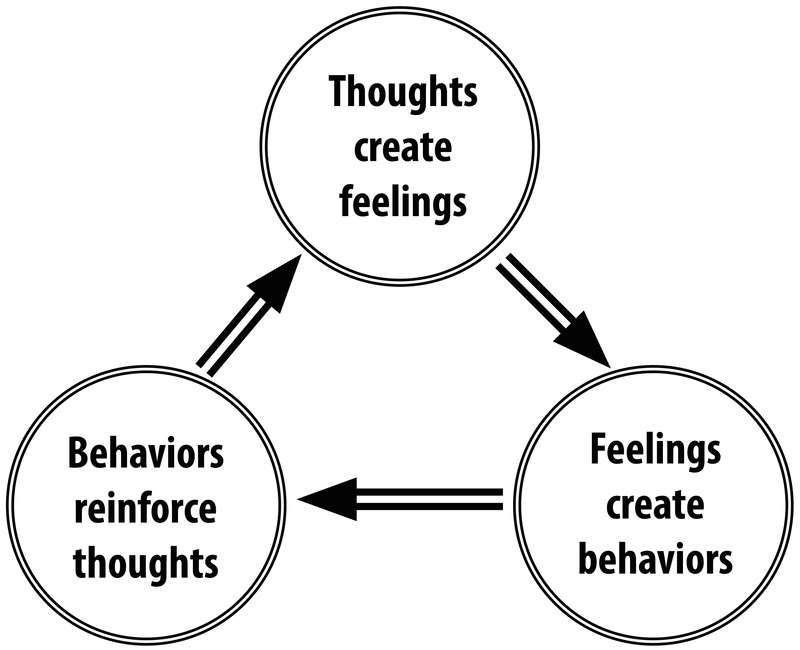

Although the behavioural and cognitive models have separate origins, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which combines elements of both, has gained more widespread support and practice. CBT refers to a family of therapeutic approaches whose goal is to alleviate psychological symptoms by changing their underlying cognitions and behaviors. The premise of CBT is that thoughts, behaviors, and emotions interact and contribute to various mental disorders. For example, let’s consider how a CBT therapist would view a patient who compulsively washes her hands for hours every day. First, the therapist would identify the patient’s maladaptive thought: “If I don’t wash my hands like this, I will get a disease and die.” The therapist then identifies how this maladaptive thought leads to a maladaptive emotion: the feeling of anxiety when her hands aren’t being washed. And finally, this maladaptive emotion leads to the maladaptive behavior: the patient washing her hands for hours every day.

CBT is a present-focused therapy (i.e., focused on the “now” rather than causes from the past, such as childhood relationships) that uses behavioral goals to improve one’s mental illness. Often, these behavioral goals involve between-session homework assignments. For example, the therapist may give the hand-washing patient a worksheet to take home; on this worksheet, the woman is to write down every time she feels the urge to wash her hands, how she deals with the urge, and what behavior she replaces that urge with. When the patient has her next therapy session, she and the therapist review her “homework” together. CBT is a relatively brief intervention of 12 to 16 weekly sessions, closely tailored to the nature of the psychopathology and treatment of the specific mental disorder. And, as the empirical data shows, CBT has proven to be highly efficacious for virtually all psychiatric illnesses (Hofmann, Asnaani, Vonk, Sawyer, & Fang, 2012).

History of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

CBT developed from clinical work conducted in the mid-20th century by Dr. Aaron T. Beck, a psychiatrist, and Albert Ellis, a psychologist. Beck used the term automatic thoughts to refer to the thoughts depressed patients report experiencing spontaneously. He observed that these thoughts arise from three belief systems, or schemas: beliefs about the self, beliefs about the world, and beliefs about the future. In treatment, therapy initially focuses on identifying automatic thoughts (e.g., “If I don’t wash my hands constantly, I’ll get a disease”), testing their validity, and replacing maladaptive thoughts with more adaptive thoughts (e.g., “Washing my hands three times a day is sufficient to prevent a disease”). In later stages of treatment, the patient’s maladaptive schemas are examined and modified. Ellis (1957) took a comparable approach, in what he called rational-emotive-behavioral therapy (REBT), which also encourages patients to evaluate their own thoughts about situations.

Techniques in CBT

Beck and Ellis strove to help patients identify maladaptive appraisals, or the untrue judgments and evaluations of certain thoughts. For example, if it’s your first time meeting new people, you may have the automatic thought, “These people won’t like me because I have nothing interesting to share.” That thought itself is not what’s troublesome; the appraisal (or evaluation) that it might have merit is what’s troublesome. The goal of CBT is to help people make adaptive, instead of maladaptive, appraisals (e.g., “I do know interesting things!”). This technique of reappraisal, or cognitive restructuring, is a fundamental aspect of CBT. With cognitive restructuring, it is the therapist’s job to help point out when a person has an inaccurate or maladaptive thought, so that the patient can either eliminate it or modify it to be more adaptive.

In addition to thoughts, though, another important treatment target of CBT is maladaptive behavior. Every time a person engages in maladaptive behavior (e.g., never speaking to someone in new situations), he or she reinforces the validity of the maladaptive thought, thus maintaining or perpetuating the psychological illness. In treatment, the therapist and patient work together to develop healthy behavioral habits (often tracked with worksheet-like homework), so that the patient can break this cycle of maladaptive thoughts and behaviors.

For many mental health problems, especially anxiety disorders, CBT incorporates what is known as exposure therapy. During exposure therapy, a patient confronts a problematic situation and fully engages in the experience instead of avoiding it. For example, imagine a man who is terrified of spiders. Whenever he encounters one, he immediately screams and panics. In exposure therapy, the man would be forced to confront and interact with spiders, rather than simply avoiding them as he usually does. The goal is to reduce the fear associated with the situation through extinction learning, a neurobiological and cognitive process by which the patient “unlearns” the irrational fear. For example, exposure therapy for someone terrified of spiders might begin with him looking at a cartoon of a spider, followed by him looking at pictures of real spiders, and later, him handling a plastic spider. After weeks of this incremental exposure, the patient may even be able to hold a live spider. After repeated exposure (starting small and building one’s way up), the patient experiences less physiological fear and maladaptive thoughts about spiders, breaking his tendency for anxiety and subsequent avoidance.

Advantages and Disadvantages of CBT

CBT interventions tend to be relatively brief, making them cost-effective for the average consumer. In addition, CBT is an intuitive treatment that makes logical sense to patients. It can also be adapted to suit the needs of many different populations. One disadvantage, however, is that CBT does involve significant effort on the patient’s part, because the patient is an active participant in treatment. Therapists often assign “homework” (e.g., worksheets for recording one’s thoughts and behaviors) between sessions to maintain the cognitive and behavioral habits the patient is working on. The greatest strength of CBT is the abundance of empirical support for its effectiveness. Studies have consistently found CBT to be equally or more effective than other forms of treatment, including medication and other therapies (Butler, Chapman, Forman, & Beck, 2006; Hofmann et al., 2012). For this reason, CBT is considered a first-line treatment for many mental disorders.

Focus: Topic: Pioneers of CBT

The central notion of CBT is the idea that a person’s behavioral and emotional responses are causally influenced by one’s thinking. The stoic Greek philosopher Epictetus is quoted as saying, “men are not moved by things, but by the view they take of them.” Meaning, it is not the event per se, but rather one’s assumptions (including interpretations and perceptions) of the event that are responsible for one’s emotional response to it. Beck calls these assumptions about events and situations automatic thoughts (Beck, 1979), whereas Ellis (1962) refers to these assumptions as self-statements. The cognitive model assumes that these cognitive processes cause the emotional and behavioral responses to events or stimuli. This causal chain is illustrated in Ellis’s ABC model, in which A stands for the antecedent event, B stands for belief, and C stands for consequence. During CBT, the person is encouraged to carefully observe the sequence of events and the response to them, and then explore the validity of the underlying beliefs through behavioral experiments and reasoning, much like a detective or scientist.

Acceptance and Mindfulness-Based Approaches

Unlike the preceding therapies, which were developed in the 20th century, this next one was born out of age-old Buddhist and yoga practices. Mindfulness, or a process that tries to cultivate a nonjudgmental, yet attentive, mental state, is a therapy that focuses on one’s awareness of bodily sensations, thoughts, and the outside environment. Whereas other therapies work to modify or eliminate these sensations and thoughts, mindfulness focuses on nonjudgmentally accepting them (Kabat-Zinn, 2003; Baer, 2003). For example, whereas CBT may actively confront and work to change a maladaptive thought, mindfulness therapy works to acknowledge and accept the thought, understanding that the thought is spontaneous and not what the person truly believes. There are two important components of mindfulness: (1) self-regulation of attention, and (2) orientation toward the present moment (Bishop et al., 2004). Mindfulness is thought to improve mental health because it draws attention away from past and future stressors, encourages acceptance of troubling thoughts and feelings, and promotes physical relaxation.

Techniques in Mindfulness-Based Therapy

Psychologists have adapted the practice of mindfulness as a form of psychotherapy, generally called mindfulness-based therapy (MBT). Several types of MBT have become popular in recent years, including mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) (e.g., Kabat-Zinn, 1982) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) (e.g., Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002).

MBSR uses meditation, yoga, and attention to physical experiences to reduce stress. The hope is that reducing a person’s overall stress will allow that person to more objectively evaluate his or her thoughts. In MBCT, rather than reducing one’s general stress to address a specific problem, attention is focused on one’s thoughts and their associated emotions. For example, MBCT helps prevent relapses in depression by encouraging patients to evaluate their own thoughts objectively and without value judgment (Baer, 2003). Although cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) may seem similar to this, it focuses on “pushing out” the maladaptive thought, whereas mindfulness-based cognitive therapy focuses on “not getting caught up” in it. The treatments used in MBCT have been used to address a wide range of illnesses, including depression, anxiety, chronic pain, coronary artery disease, and fibromyalgia (Hofmann, Sawyer, Witt & Oh, 2010).

Mindfulness and acceptance—in addition to being therapies in their own right—have also been used as “tools” in other cognitive-behavioral therapies, particularly in dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) (e.g., Linehan, Amstrong, Suarez, Allmon, & Heard, 1991). DBT, often used in the treatment of borderline personality disorder, focuses on skills training. That is, it often employs mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy practices, but it also works to teach its patients “skills” they can use to correct maladaptive tendencies. For example, one skill DBT teaches patients is called distress tolerance—or, ways to cope with maladaptive thoughts and emotions in the moment. For example, people who feel an urge to cut themselves may be taught to snap their arm with a rubber band instead. The primary difference between DBT and CBT is that DBT employs techniques that address the symptoms of the problem (e.g., cutting oneself) rather than the problem itself (e.g., understanding the psychological motivation to cut oneself). CBT does not teach such skills training because of the concern that the skills—even though they may help in the short-term—may be harmful in the long-term, by maintaining maladaptive thoughts and behaviors.

DBT is founded on the perspective of a dialectical worldview. That is, rather than thinking of the world as “black and white,” or “only good and only bad,” it focuses on accepting that some things can have characteristics of both “good” and “bad.” So, in a case involving maladaptive thoughts, instead of teaching that a thought is entirely bad, DBT tries to help patients be less judgmental of their thoughts (as with mindfulness-based therapy) and encourages change through therapeutic progress, using cognitive-behavioral techniques as well as mindfulness exercises.

Another form of treatment that also uses mindfulness techniques is acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999). In this treatment, patients are taught to observe their thoughts from a detached perspective (Hayes et al., 1999). ACT encourages patients not to attempt to change or avoid thoughts and emotions they observe in themselves, but to recognize which are beneficial and which are harmful. However, the differences among ACT, CBT, and other mindfulness-based treatments are a topic of controversy in the current literature.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Mindfulness-Based Therapy

Two key advantages of mindfulness-based therapies are their acceptability and accessibility to patients. Because yoga and meditation are already widely known in popular culture, consumers of mental healthcare are often interested in trying related psychological therapies. Currently, psychologists have not come to a consensus on the efficacy of MBT, though growing evidence supports its effectiveness for treating mood and anxiety disorders. For example, one review of MBT studies for anxiety and depression found that mindfulness-based interventions generally led to moderate symptom improvement (Hofmann et al., 2010).

Emerging Treatment Strategies

With growth in research and technology, psychologists have been able to develop new treatment strategies in recent years. Often, these approaches focus on enhancing existing treatments, such as cognitive-behavioral therapies, through the use of technological advances. For example, internet- and mobile-delivered therapies make psychological treatments more available, through smartphones and online access. Clinician-supervised online CBT modules allow patients to access treatment from home on their own schedule—an opportunity particularly important for patients with less geographic or socioeconomic access to traditional treatments. Furthermore, smartphones help extend therapy to patients’ daily lives, allowing for symptom tracking, homework reminders, and more frequent therapist contact.

Another benefit of technology is cognitive bias modification. Here, patients are given exercises, often through the use of video games, aimed at changing their problematic thought processes. For example, researchers might use a mobile app to train alcohol abusers to avoid stimuli related to alcohol. One version of this game flashes four pictures on the screen—three alcohol cues (e.g., a can of beer, the front of a bar) and one health-related image (e.g., someone drinking water). The goal is for the patient to tap the healthy picture as fast as s/he can. Games like these aim to target patients’ automatic, subconscious thoughts that may be difficult to direct through conscious effort. That is, by repeatedly tapping the healthy image, the patient learns to “ignore” the alcohol cues, so when those cues are encountered in the environment, they will be less likely to trigger the urge to drink. Approaches like these are promising because of their accessibility, however they require further research to establish their effectiveness.

Yet another emerging treatment employs CBT-enhancing pharmaceutical agents. These are drugs used to improve the effects of therapeutic interventions. Based on research from animal experiments, researchers have found that certain drugs influence the biological processes known to be involved in learning. Thus, if people take these drugs while going through psychotherapy, they are better able to “learn” the techniques for improvement. For example, the antibiotic d-cycloserine improves treatment for anxiety disorders by facilitating the learning processes that occur during exposure therapy. Ongoing research in this exciting area may prove to be quite fruitful.

Conclusion

Throughout human history we have had to deal with mental illness in one form or another. Over time, several schools of thought have emerged for treating these problems. Although various therapies have been shown to work for specific individuals, cognitive behavioral therapy is currently the treatment most widely supported by empirical research. Still, practices like psychodynamic therapies, person-centered therapy, mindfulness-based treatments, and acceptance and commitment therapy have also shown success. And, with recent advances in research and technology, clinicians are able to enhance these and other therapies to treat more patients more effectively than ever before. However, what is important in the end is that people actually seek out mental health specialists to help them with their problems. One of the biggest deterrents to doing so is that people don’t understand what psychotherapy really entails. Through understanding how current practices work, not only can we better educate people about how to get the help they need, but we can continue to advance our treatments to be more effective in the future.

Outside Resources

Article: A personal account of the benefits of mindfulness-based therapy https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/jan/11/julie-myerson-mindfulness-based-cognitive-therapy

Article: The Effect of Mindfulness-Based Therapy on Anxiety and Depression: A Meta-Analytic Review https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2848393/

Video: An example of a person-centered therapy session.

Video: Carl Rogers, the founder of the humanistic, person-centered approach to psychology, discusses the position of the therapist in PCT.

Video: CBT (cognitive behavioral therapy) is one of the most common treatments for a range of mental health problems, from anxiety, depression, bipolar, OCD or schizophrenia. This animation explains the basics and how you can decide whether it’s best for you or not.

Web: An overview of the purpose and practice of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) http://psychcentral.com/lib/in-depth-cognitive-behavioral-therapy/

Web: The history and development of psychoanalysis http://www.freudfile.org/psychoanalysis/history.html

Discussion Questions

- Psychoanalytic theory is no longer the dominant therapeutic approach, because it lacks empirical support. Yet many consumers continue to seek psychoanalytic or psychodynamic treatments. Do you think psychoanalysis still has a place in mental health treatment? If so, why?

- What might be some advantages and disadvantages of technological advances in psychological treatment? What will psychotherapy look like 100 years from now?

- Some people have argued that all therapies are about equally effective, and that they all affect change through common factors such as the involvement of a supportive therapist. Does this claim sound reasonable to you? Why or why not?

- When choosing a psychological treatment for a specific patient, what factors besides the treatment’s demonstrated efficacy should be taken into account?

References

Baer, R. (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 125–143.

Beck, A. T. (1979). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York, NY: New American Library/Meridian.

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., Segal, Z. V., Abbey, S., Speca, M., Velting, D., & Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11, 230–241.

Boettcher, H., Hofmann, S. G., & Wu, Q. J. (2020). Therapeutic Orientations. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/fjtnpwsk.

Bridley, A. & Daffin, L. W. Jr. (2018). The Behavioural Model. In C. Cuttler (Ed), Essentials of Abnormal Psychology. Washington State University. Retrieved from https://opentext.wsu.edu/abnormalpsychology/).

Bridley, A. & Daffin, L. W. Jr. (2018). The Cognitive Model. In C. Cuttler (Ed), Essentials of Abnormal Psychology. Washington State University. Retrieved from https://opentext.wsu.edu/abnormalpsychology/).

Butler, A. C., Chapman, J. E., Forman, E. M., & Beck, A. T. (2006). The empirical status of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 17–31.

Cuijpers, P., Driessen, E., Hollon, S.D., van Oppen, P., Barth, J., & Andersson, G. (2012). The efficacy of non-directive supportive therapy for adult depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 280–291.

Driessen, E., Cuijpers, P., de Maat, S. C. M., Abbass, A. A., de Jonghe, F., & Dekker, J. J. M. (2010). The efficacy of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 25–36.

Ellis, A. (1962). Reason and emotion in psychotherapy. New York, NY: Lyle Stuart.

Ellis, A. (1957). Rational psychotherapy and individual psychology. Journal of Individual Psychology, 13, 38–44.

Freud, S. (1955). The interpretation of dreams. London, UK: Hogarth Press (Original work published 1900).

Freud, S. (1955). Studies on hysteria. London, UK: Hogarth Press (Original work published 1895).

Freud. S. (1955). Beyond the pleasure principle. H London, UK: Hogarth Press (Original work published 1920).

Friedli, K., King, M. B., Lloyd, M., & Horder, J. (1997). Randomized controlled assessment of non-directive psychotherapy versus routine general-practitioner care. Lancet, 350, n1662–1665.

Hakimian, M., & D’Souza, L. (2016). Effectiveness of systematic desensitization and cognitive behavior therapy on reduction of obsessive compulsive disorder symptoms: A comparative study. European Online Journal of Natural and Social Sciences, 5(1), 147-154. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/230044827.pdf.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. New\\nYork, NY: Guilford Press.

Hofmann, S. G., Asnaani, A., Vonk, J. J., Sawyer, A. T., & Fang, A. (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36, 427–440.

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A., & Oh, D. (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 169–183.

Jones, M. C. (1924). The elimination of children’s fears. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 7(5), 382-390.

Kabat-Zinn J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 144–156.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1982). An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients\\nbased on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary results. General Hospital Psychiatry, 4, 33–47.

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age of onset distribution of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 593–602.

Leichsenring, F., & Rabung, S. (2008). Effectiveness of long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association, 300, 1551–1565.

Linehan, M. M., Amstrong, H.-E., Suarez, A., Allmon, D., & Heard, H. L. (1991). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically suicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48, 1060–1064.

Masoumeh, H., & Lancy, D. S. (2016). Effectiveness of systematic desensitization and cognitive behaviour therapy in reduction of depression among obsessive compulsive disorder patients-A Comparative Study. International Journal of Psychology and Psychiatry, 4(1), 56-71.

Nasser, M. (1987). Psychiatry in ancient Egypt. Bulletin of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, 11, 420-422.

Norcross, J. C. & Goldfried, M. R. (2005). Handbook of Psychotherapy Integration. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Rogers, C. (1951). Client-Centered Therapy. Cambridge, MA: Riverside Press.

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy\\nfor Depression: A New Approach to Preventing Relapse. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Watson, J. & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3, 1-4.

Wolpe, J. (1997). From psychoanalytic to behavioral methods in anxiety disorders: A continuing evolution.Brunner/Mazel.