2 History of Libraries

We have already explored several terms that may have other meanings in external fields of research but that have specific meanings in library science. In order for you to understand the terms and trends in the field, you will need to develop a knowledge of its lexicon. A Lexicon is a specialized collection of words that are unique, or at least have a unique meaning, for a particular field. For example, the word “Record” has been defined as a formatted collection of all of an item’s metadata. You would not, however, refer to a medical history record as a collection of all metadata about a patient. A medical history record is a chart or data collection about a patient’s treatments and health throughout a given period of time. These definitions are similar, and comparable, but are not entirely appropriate when applied to each others’ fields.

Libraries in the Ancient and Pre-American World

Ironically, in order to understand the concept of libraries you will need to understand a different definition of the word “lexicon.” Originally, it was a term for a dictionary or thesaurus that recorded all of the words in a given language. Ancient civilizations used to create lexicons with each others’ languages as a type of training manual. These were among the first books to be written down. Many ancient Greek lexicons exist.

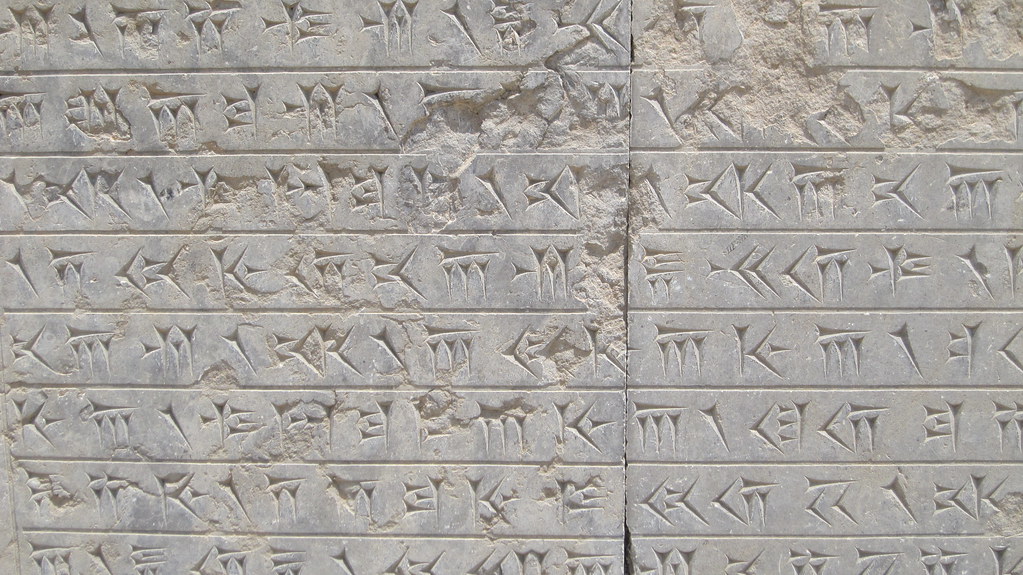

The first writing system, however, was not the Greek language. The honor of creating the first written language belongs to the ancient kingdom of Sumer. Sumerians developed a system of writing called Cuneiform. This language utilized a pattern of symbols carved into stone and clay. The earliest examples of cuneiform writing describe day-to-day activities such as purchasing groceries and larger matters such as settling land disputes. Cuneiform usage spread throughout the area and became standard in several other kingdoms during the Bronze Age.

Papyrus was the first light and easily-transportable material on which one could write information. This plant material was pressed into sheets by the Ancient Egyptians around 2900 B.C.E. It became the dominant medium for writing things down throughout the ancient world, even being used by the ancient Greeks. Papyrus documents were not folded into the book-shaped form we know today. Rather, they were rolled together.

The standard form of books came much later. Religious scholars and monks wrote texts on sheets of paper, and some of these were folded into small books called “quartos.” After a long time of handwritten text and large block printing, the Printing Revolution came in the 1450s, when Johannes Gutenberg printed his Gutenberg Bible. Many books, including previous works and new ones, swiftly followed the Gutenberg Bible. Information spread throughout the Western world, chiefly carried by books.

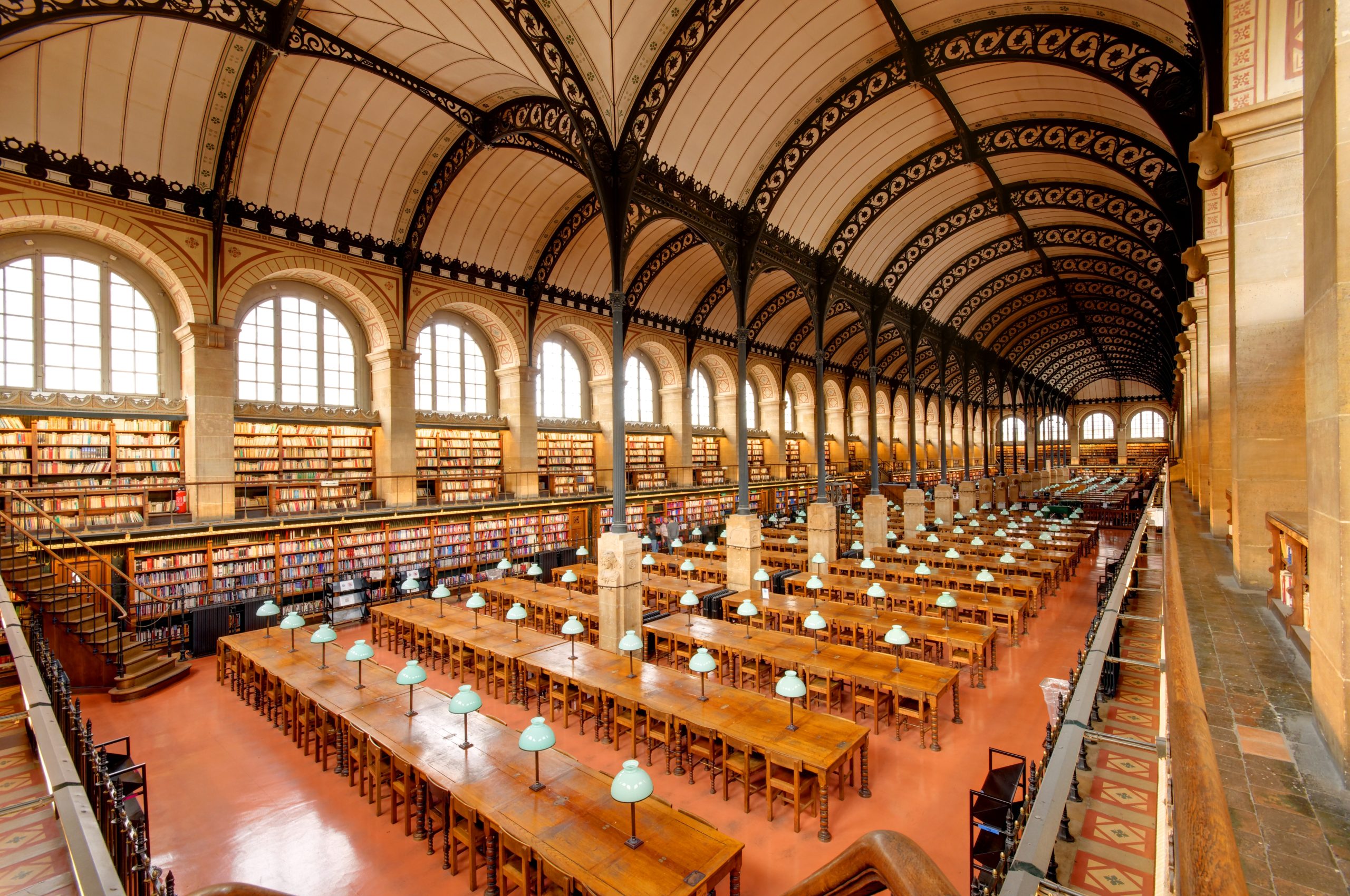

During the 17th and 18th centuries, some of the more important European libraries were founded, such as the Bodleian Library at Oxford, the British Museum Library in London, the Mazarine Library and the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève in Paris, the Austrian National Library in Vienna, the National Central Library in Florence, the Prussian State Library in Berlin, the Załuski Library in Warsaw and the M.E. Saltykov-Shchedrin State Public Library of St Petersburg. [1] The 18th century is when we see the beginning of the modern public library. In France, the French Revolution saw the confiscation in 1789 of church libraries and rich nobles’ private libraries, and their collections became state property. The confiscated stock became part of a new national library – the Bibliothèque Nationale. Two famous librarians, Hubert-Pascal Ameilhon and Joseph Van Praet, selected and identified over 300,000 books and manuscripts that became the property of the people in the Bibliothèque Nationale. During the French Revolution, librarians were solely responsible for the bibliographic planning of the nation. Out of this came the implementation of the concept of library service – the democratic extension of library services to the general public regardless of wealth or education.[2]

Libraries in the United States

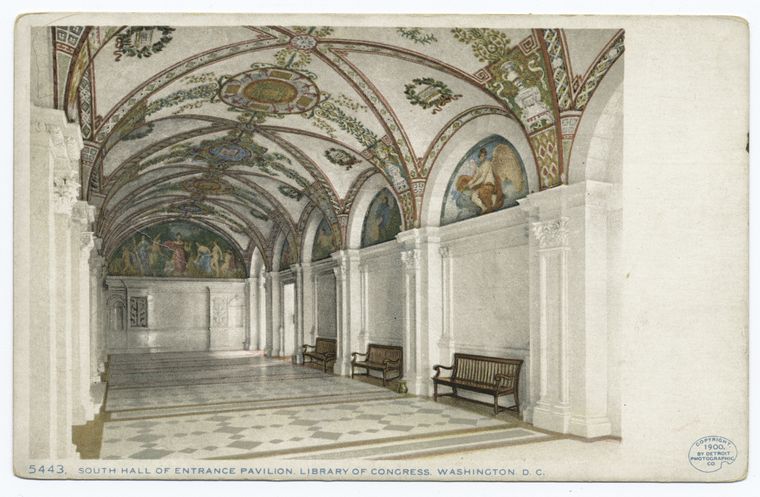

Libraries were an important part of the beginning of the United States. In addition to academic libraries essential to educational systems created in colonial settlements in the American colonies, libraries in private residences provided access to much of the information necessary to foment the American Revolution and create the first American government. Libraries are so important to the federal government that in 1800, John Adams approved the creation of a Library of Congress. This library was damaged by the fire started by British soldiers in the War of 1812, but it was more than replenished when Thomas Jefferson donated his personal library of almost 6,500 books to its collections. Physical books were the main holdings of the library, and its scope was limited to members of Congress, although the public was welcome to look at popular books. In 1897, the library received its own building and became the largest library in the entire world at that time.

Since then, the Library of Congress has adapted and evolved into a unique, global institution, widely known for its free, non-partisan service to Congress, librarians, scholars, and the public—in the United States and around the world. It has become the gold standard for libraries everywhere. This is why we follow the procedures, practices, and classifying norms we do–because the Library of Congress has collaborated with professionals around the world to create internationally-recognized standards.

Institutions and Realities of the Modern World of Librarianship

The other major organizations in modern librarianship in the United States are OCLC and the American Library Association. The ALA was founded on October 6, 1876. Its purpose was originally to facilitate connections between librarians rather than serve as a massive organization and network for libraries as institutions. Gradually, it morphed into that latter definition. It promotes the use of librarianship and information literacy education to encourage advocacy, diversity, and lifelong learning. In addition to the norms of LCC, the Code of Ethics and the Bill of Rights provided by the ALA are the guiding documents of the profession. Librarians in all types of libraries adhere to these principles.

OCLC, which used to refer to the Ohio College Library Center and then the Online Computer Library Center, now stands for nothing. Literally. That is the name of the organization. This group produces the most effective trainings and products for librarianship. They are the force behind Interlibrary Loan, WebDewey, Connexion, and WorldCat. While they have somewhat misappropriated their influence to form a monopoly, they have also created tools that are invaluable. The Library of Congress Classification Web service can be used in conjunction with these to help in many technical services aspects of librarianship. WorldCat can even help with some patron service aspects as well.

In today’s modern world, there are more information and data carriers than books or other verbal media. Audiovisual, audio, and image carriers are also wonderful ways to obtain data and information and cement knowledge into our minds. This book explores the many different types of libraries and the similar functions and services they all offer to their patrons.

When we think of libraries today, we usually visualize the public library. However, the public library is a relatively new development in the history of library science. While books and libraries are typically seen as the great equalizer in terms of information, the original libraries only served the wealthy members of society. Thus, power that was originally in the hands of the clergy because of lack of information only spread to the wealthy and educated upper class. Libraries only gave items to those who sponsored their collections and maintenance. This original library iteration was known as the Subscription Library. Although subscription libraries exist today, member institutions often extend their privileges to students and others. For example, a library may create an institutional account to the “subscription library”-esque site of Encyclopedia Britannica. All of its members can thus access all of Encyclopedia Britannica’s pages.

How did the first libraries categorize and catalog their holdings and collections? There were no set criteria for cataloging items or works. Organization depended largely on the whim of the local librarian. The first major break from this trend was the creation of the Dewey Decimal Classification System by Melvil Dewey in the late nineteenth century. This system is currently in its 23rd iteration. It is increasingly being replaced by the Library of Congress Classification System. However, the DDC is still significant in that it was the first comprehensive attempt to categorize all knowledge contained in library items.

- Stockwell, Foster (2000). A History of Information and Storage Retrieval. ISBN 0-7864-0840-5. ↵

- Mukherjee, A. K. (1966) Librarianship: its Philosophy and History. Asia Publishing House; p. 112. ↵

This word has two meanings:

A dictionary

A collection of vocabulary words and phrases that are important to a specific group of people. Words in this collection are often referred to colloquially as "jargon" or "lingo."

The glossary of this book follows the second definition. Many of these words have definitions that are unique to the world of librarianship (for example, MARC). Other definitions are similar to external definitions (for example, customer service).

The first symbols recorded on a movable record. This system of writing was invented by the Sumerians around 3200 B.C.E. Scribes wrote these symbols into stone walls or clay tablets.

This is the first material on which words or ideas were written. It was invented around the 2900 BCE in Egypt. From there, its use spread to Ancient Greece and other kingdoms. It was the dominant medium for writing until paper was invented in China around three and a half thousand years later.

One of the first books printed by Johannes Gutenberg on a printing press in the 1450s. This was proof that information and data was spreadable to people by other means than handwriting. The proliferation of this Bible was made even more significant by the fact that the type blocks used to create the Bible were mass-produced. After the creation of this Bible, many printed books followed.

A library whose access extends only to those who pay a subscription fee. Under certain circumstances, members can extend their membership to other interested parties for a limited time or to a limited scope of materials. This type of library is similar to a database whose data can only be accessed by paying individuals or institutions.

A system created by Melvil Dewey in the late nineteenth century to classify all knowledge into ten broad categories. This system has been modified twenty three times until the current iteration, Dewey Decimal System Edition 23, was created in early 2010s. It is often used on its own and in conjunction with the Library of Congress Classification System.

Feedback/Errata