14 Shelving, Shelflisting, and Work and Author Orders

After the assignation of the call number and the subject heading comes the wonderful task of shelving the book. This may seem to be intuitive, and it usually is for the Dewey Decimal Classification system. Therefore, we will not spend time examining that system. You simply place your book according to numerical order and the alphabetical order.

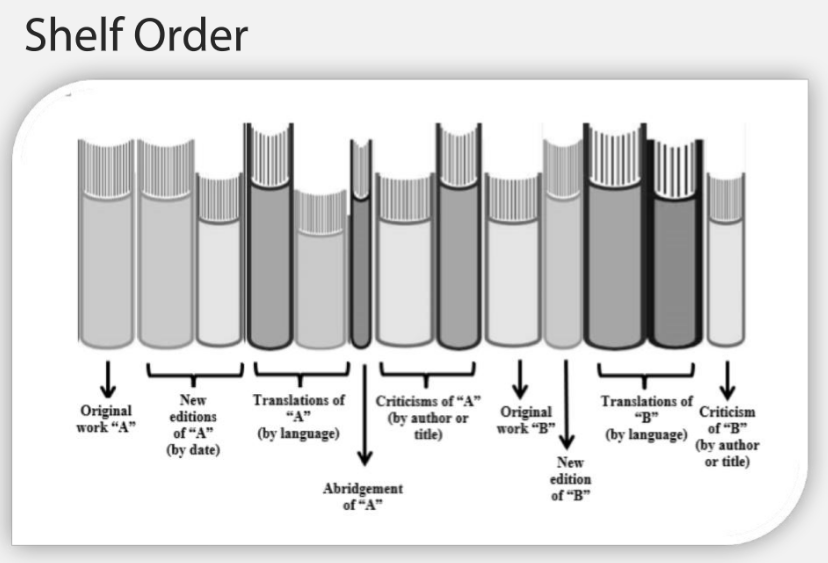

The Library of Congress, however, is another story. You might have already guessed this by the fact that the chapter on Classification Web is almost three times longer than OCLC Connexion and four hundred words longer than WebDewey. Just as coming up with a number in this system is more difficult, so shelving can be less intuitive. Fortunately, the Library of Congress has provided guidelines and regulations for assigning shelf places. An original work is placed first on a shelf, followed by:

- Subsequent editions

- Translations, also by editions of the original work

- Abridgements of the work, also by edition

- Criticisms or analyses of the original work

- Related works, whose editions, translations, abridgments, and criticisms also follow the same process.

- When a corporation or an individual is the subject of a work, those works should be given the same Cutter number as their own work products. They should be placed following the works created by the works’ subject. In other words, a biography of Boris Yeltsin would follow any work by Boris Yeltsin.

However, where do the original works go? There are a few rules for shelving that are the same as those for the Classification system:

- Nothing comes before something. In other words, works with only “V” should come before those that have “VB.” Additionally, 17 should come before 17.1, which should in turn come before 17.13.

- First Cutter numbers are the same as decimal numbers. Alphanumerical order is also followed (A comes before C, etc.).

- Cutter numbers are arranged discretely. Arrange works completely by the first Cutter number and then arrange works by the second Cutter number within the category of the first Cutter number. The second Cutter number is also called the first part of the item number.

- The last Cutter number, which is also called the second part of the item number, is the year. This should be arranged in the same way that the second Cutter number is arranged in categories of the first Cutter numbers. Chronological order should always be followed.

- At times, multiple works will be created by the same author in the same year. Some people will create unique first-or-second Cutter numbers. Others will follow another system which is more consistent. They will place lowercase letters for each work after the original one (2010, 2010a, 2010 b, etc.). These should be placed in alphabetical order.

- Remember again that nothing comes before something. In that spirit, items with one Cutter number should placed before those with two. Items with two should be placed before those with no year.

If a Cutter number includes both uppercase and lowercase letters, as some might do with the Dewey Decimal System, best practice is to file those discretely and alphabetically, word-by-word and letter-by-letter. Spaces and periods, hyphens, should be treated the same, and are used to signify yet another discrete unit in a call number. On the other hand, apostrophes should be completely ignored. If a word is an abbreviation of a larger word, such as Mt. or St., that spelling, and not the larger word, should be used.

When categorizing works by title, all initial articles in any language should be completely ignored. They should not be included in the catalog, or should be included after the rest of the title, preceded by a comma.

Compounded surnames, whether or not they have a hyphen, should be listed in author lists with the first part of the surname preceding the second. For that matter, surnames should precede first names, again being separated by a colon.

Diacritics and punctuation in titles and names should be completely ignored when creating shelf lists. If a name includes a character that is not typical, the Library of Congress Classification and Shelflisting Manual G100 section should be followed.

Another factor is the order of numbers and letters in initial order. Initial numerals should be shelflisted before, not after, letters. If numerals are after a name, which virtually only occurs in years of Authority Control Names, they should be listed in numerical order as well. If a number is part of a title, it should be listed before years.

Yet another factor is the ampersand symbol. When it appears at the beginning of a title, which is rare, it should be given precedence over numerals, which means it comes first in shelflisting order.

These rules can be helpful for Dewey Decimal Classification system shelflisting and ordering as well. For example, the suggestion to ignore diacritics and focus on the letter can help people who are making Cutter numbers in the DDC with authors whose first letter of their surname includes a diacritic.

Further Divisions

Dividing items by genre, language, and/or format may be necessary for ease of access. Whether an item is cataloged according to the LCC or DCC, these types of subdivisions may be necessary. This is why the section on these divisions is here rather than with sections on call number creation. Below are some rules for Dewey format and fiction division that have been adapted in some locations for other schema. For example, even though the College of Southern Idaho Library utilizes LCC, we still designate our Spanish materials with an “SPA” at the beginning of the call number for ease of access.

Exception: if you choose to shelve certain types of books in separate areas, then begin those call numbers with a descriptive word or abbreviation, or example: REFERENCE, LARGE, or ATLAS.

For fiction books, the first line is usually FICTION or some abbreviation (FIC., or F). Some libraries use call number labels to subdivide their fiction collections by genre, such as ROMANCE or SF, but this can get complicated because of so many cross-genre titles.

For non-book items, the first line of the call number for both fiction and non-fiction works may be a term or abbreviation indicating the format of the item. This could be something like DVD, or CD for compact discs, or Playaway for a certain format of audiobook.

Online electronic publications are an exception to the call number guidelines. An ebook that you read online or an audiobook that you download from online are not physical items. They only exist as digital bits and bytes on a computer server somewhere. You cannot direct a patron to a physical location for this kind of item, so there is no point is giving it a call number. How do you tell patrons where to find it? Give them the URL that is found in the 856 field of the MARC record.

Feedback/Errata